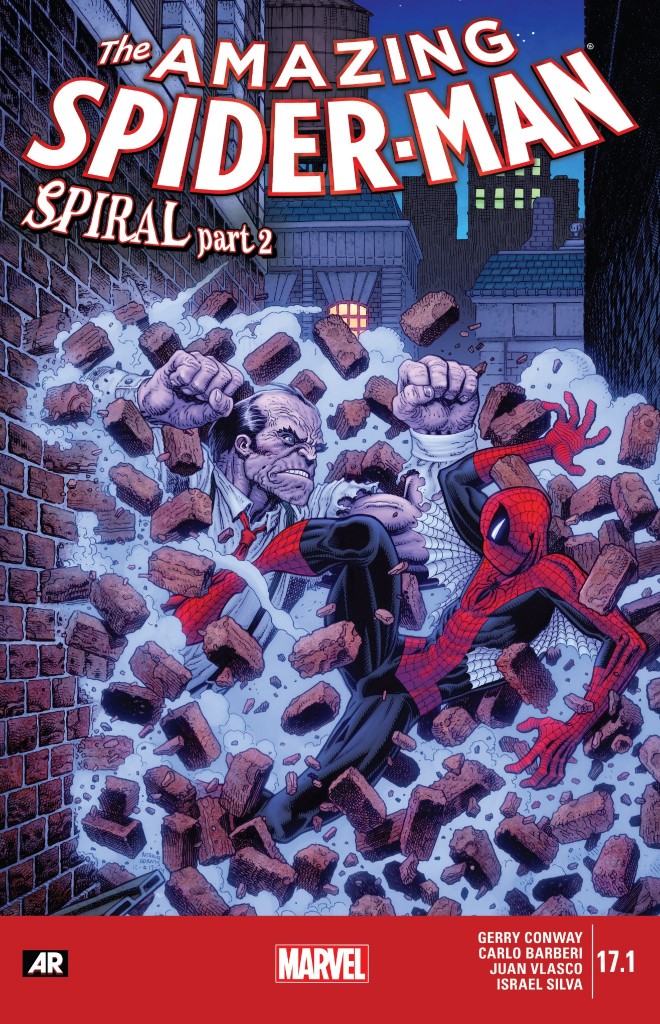

Since Amazing Spider-Man’s “Spiral” arc kicked off last month, there’s been a lot of chatter about how it has been a welcomed return to Spidey’s “street level” roots. And that’s undeniably true, especially in light of the past two years of Spider-Man storylines. But what I’ve appreciated most about what Gerry Conway and Carlo Barbieri have put together through two issues is “Spiral’s” laser-focus on characterization. This is the smartest, most nuanced multi-issue Spider-Man story I’ve read in years, and most of that stems from the fact that Conway knows exactly who he’s writing about and how the character’s actions drive the story – not the other way around.

There’s a distinction in terms of good storytelling between wanting to know what a character is going to do next versus wanting to know what’s going to happen in the story next. Both can be equally effective, but when a writer leans exclusively on the latter – aka serving story over character – it rarely leads to good results (or at least results I’m a fan of).

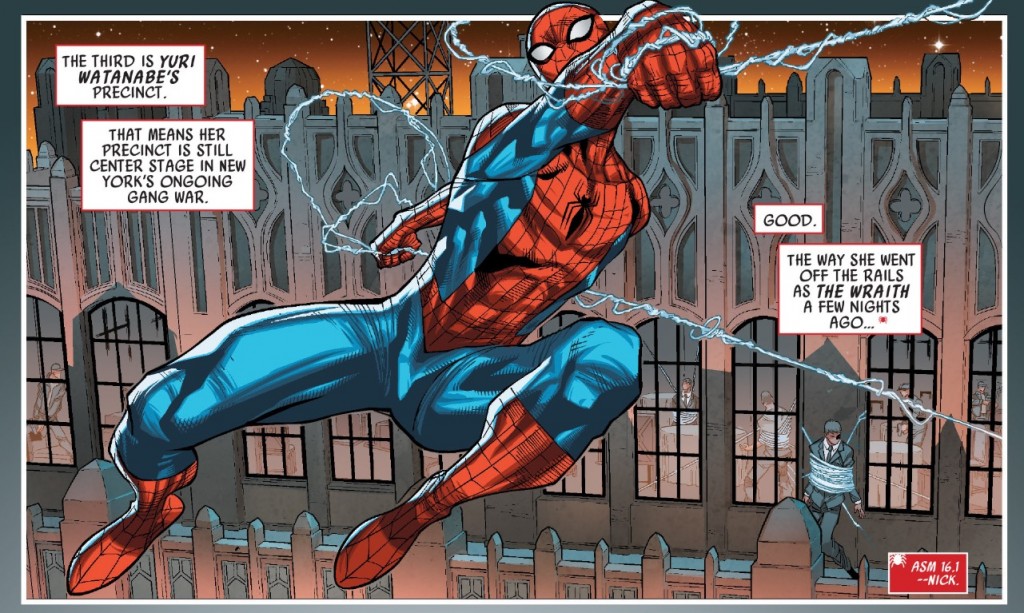

On nearly every page of Amazing Spider-Man #17.1, I found myself engaged by what the characters might do next. Conway injects a certain level of confidence and swagger into Spidey that has been missing from Spider-Man comics for a while now, but balances it with his trademark guilt – this time he finds himself reluctantly teaming-up with the Wraith because he attempts to sympathize with Yuri Watanabe’s personal tragedy regarding the death of her police partner. As a result of this character choice, there is legitimate drama and intrigue as to how far Spider-Man will allow himself to be pushed by his partner, who clearly is disinterested in playing by any book or following the rules of any system.

Meanwhile, Conway is doing some interesting things with Watanabe. She is being driven by a thirst for justice but is letting her personal emotions and anger for what happened to her partner blur the lines between virtue and vengeance. Her intentions are ultimately good – criminals like Tombstone and Hammerhead are unquestionably bad people who don’t care who they hurt as part of their war over abandoned underworld “turf.” But she aligns with another known-criminal, Mister Negative, using a shades of gray reasoning of the ends justifying the means. And when a judge who she believed to be corrupt reveals to her that he had sound, even sympathetic reasoning behind his unjust actions, she dismisses him as if she is only capable of seeing the world in stark black and white.

Such complex characterization doesn’t make it easy for the reader to determine who’s “right” or “wrong.” But some of the best stories aren’t supposed to be easy in that regard – they’re just supposed to engage the audience and leave them asking questions. At one point, Spider-Man brilliantly tells Yuri that they don’t protect turf, they protect people. But as I discussed in my last post on “Spiral,” Spider-Man himself is a masked person who operates the confines of the law. Who is he to declare the purpose/motive of vigilantism? Sure, saying you protect people not territories distinguishes what the heroes do from what underworld criminals do. But does saying it actually make it true when the end result – apprehending the crooks?

Even with its focus on characterization, ASM #17.1 is filled with moments of dynamic – and fun – action sequences. A scene like Spider-Man crashing through the skylight of the ballroom at the Hotel Knickerbocker is the kind of inspired, old-school superheroics one would have found during Conway’s inaugural run on ASM in the 1970s. Add in Spider-Man’s smartest man in the room banter, and you’re left with a comic book opening that’s both visually stimulating and humorous to read.

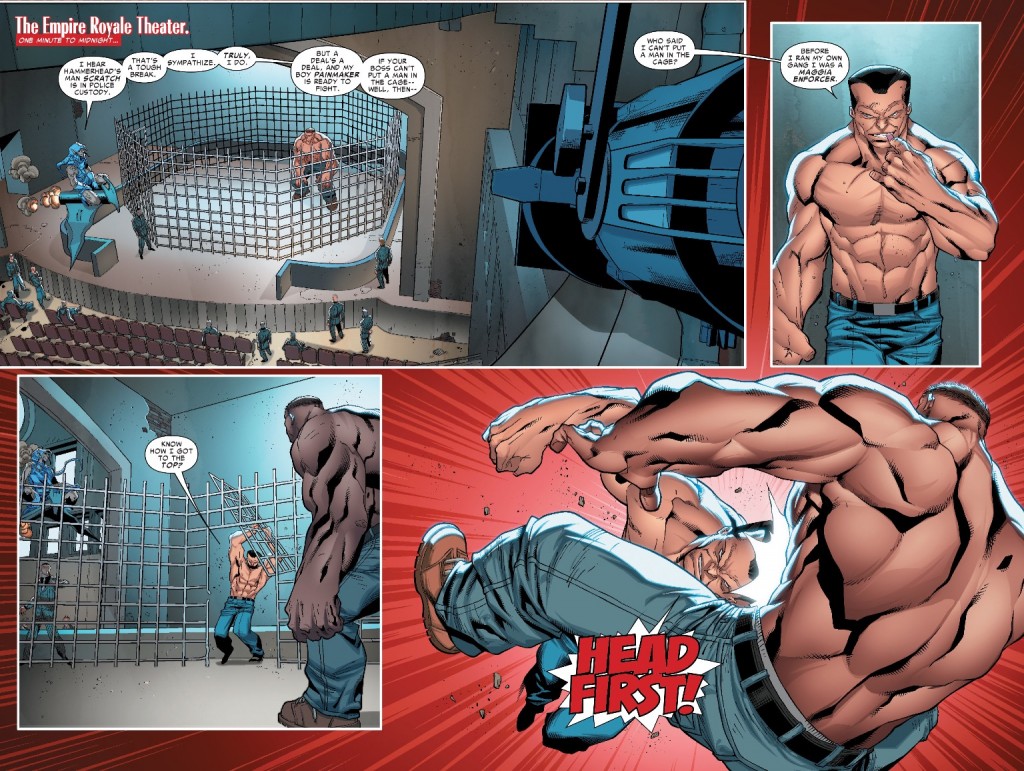

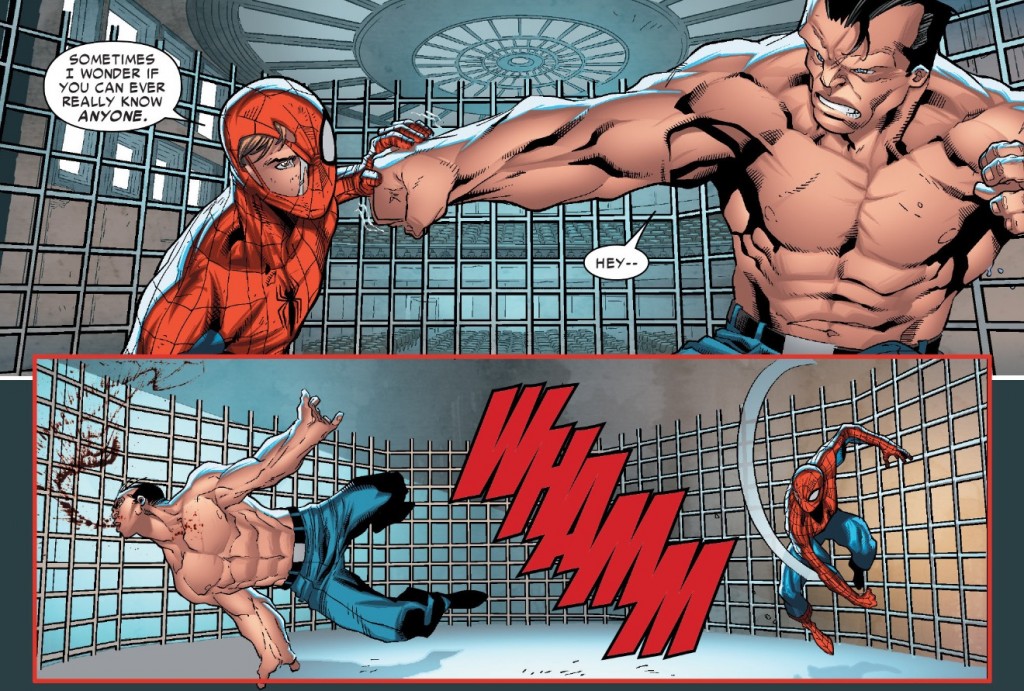

The Fight Club-esque turf battle between Hammerhead and the Goblin King was (the good kind) of comic book goofiness – Hammerhead constantly chomping down on a piece of chewing gun is an offbeat, but interesting touch – while also adding a bit of life and color to Marvel’s criminal underworld. Even on the generally excellent Daredevil on Netflix series, there’s a certain level of laziness in how many creators depict comic book gang members. They’re usually just standing around in an abandoned warehouse until the hero unexpectedly crashes in. Showing two goons walking into an octagon-shaped cage ready to kill each other like a couple of Roman gladiators is certainly far more interesting that some Maggia enforcer in a fedora, or a Yakuza ninja just standing there waiting for someone else to dictate their actions.

And not for nothing, it was nice getting to see Spider-Man capably handle himself with a brute like Hammerhead during the Fight Club scene. There’s been far too many Spidey stories over the past year that show our hero getting embarrassed by the opposition and only surviving by the skin of his teeth or the grace of his plucky sidekick Silk. Maybe having Spider-Man beat the crud out of a herald of Galactus pushes the limits of credulity a bit (though it’s still a great scene), but when I’m reading a Spider-Man comic book, I want to see the web slinger at least resemble a successful hero more often than not. I feel ridiculous even having to make that point, but could someone send a memo to the rest of the Spider-office that Spidey is allowed to win on his own merits sometimes?

Totally agree on all points. Loving these Conway issues. Feels refreshing and his characterization is spot on and I love the focus of Wraith ‘ s motives.

He gets the character and it actually feels like finally reading about THE Spider-Man introduced by Lee and Ditko so long ago instead of the bumbling idiot “inspector gadget”-like portrayal that’s been pushed too far, too often as of late.

For example, Slott is good at times but can be so off the mark at other times and uses poor logic and poor decisions by Peter/Spidey to move the narrative forward instead of letting the plot play out naturally and ends up making Spidey look like a goof.

At this point, let’s face it – Peter is an experienced and established hero. Sure, he’s not perfect but Slott tends to have him do things that undermine the character’s experiences and past.

Conway can also direct a great fight scene the likes of we haven’t seen in ASM for ages.

Overall I like Slott but some of his decisions have been poorly executed or just devices to serve the plot, irregardless if they make sense or stem from logical character choices.

What I think Conway does here though is shows he has a deeper understanding of what makes Spidey work and doesn’t have to rely on contrived plotting to move the story along.