The original Spider-Man Noir miniseries is one of those books that sounds like an interesting concept on paper, but ultimately falls short in its execution. And yet, in my three-plus years of blogging, I’ve talked/tweeted/interacted with a number of fans who absolutely adore this series. So, I guess I’ll just have to tread carefully with whatever I write here!

Actually, it’s really not that bad of a series, but I guess my mixed opinions are more of a byproduct of trying to figure out where all of the love and hype comes from. The Spider-Man Noir version of Peter Parker/Spider-Man (from Earth-90214 for those keeping score at home) has kicked off the Edge of Spider-Verse miniseries that released today, and I’m also aware that he’s one of the featured characters in the Shattered Dimension video game that a lot of people speak highly of. But since I really don’t play video games anymore unless they involve puzzles to be solved via a touch screen, I can only judge Noir Spider-Man based on the merits of his comic book stories. And that’s where things get a bit muddied.

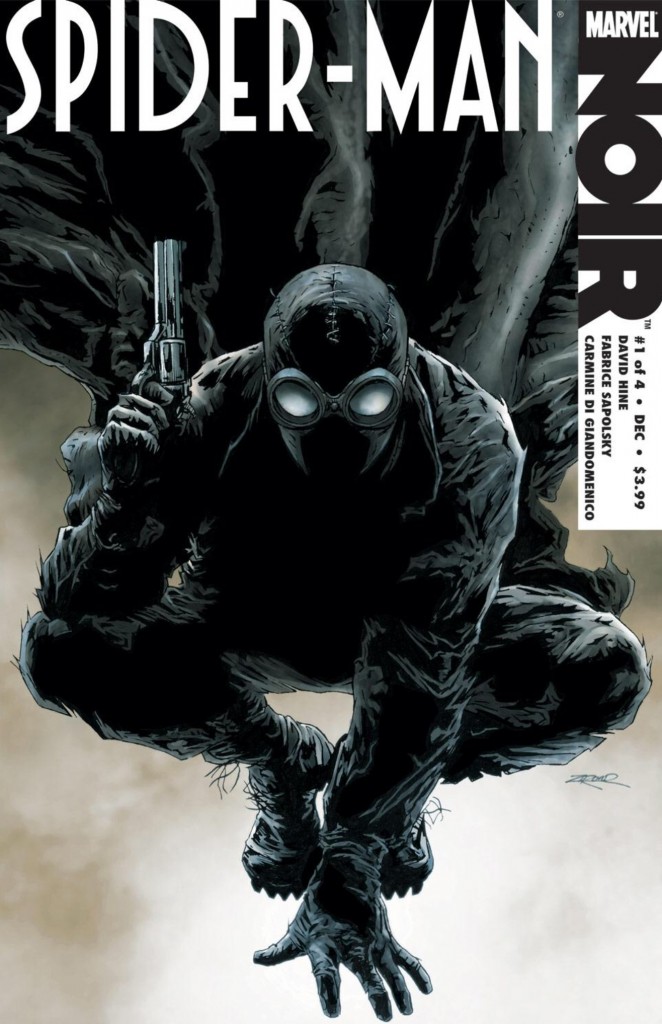

Really, all the disenchantment I have with this series stems from the use of the word “noir” in the title. I feel like ever since Frank Miller spearheaded the neo-noir movement in comics in the early 1980s with his run on Daredevil (and later ,even moreso, with his Sin City series), creators and publishers have tossed the word “noir” around without having a full grasp of its meaning. It’s literal meaning is a sub-genre of crime fiction that typically depicts sleazy, morally ambiguous or ambivalent characters. The latter part of the definition certainly applies to Spider-Man Noir, which was written by David Hine and Fabrice Sapolsky with art from Carmine Di Giandomenico. Bbut I have some questions about the “crime” elements of the story.

Certainly the series opens with a crime – Spider-Man finds himself in a precarious situation when the cops burst in on him and a dead, bullethole-riddled J. Jonah Jameson inside the Daily Bugle. But the mystery/crime-solving seemingly takes a backseat so the creative team can put their own unique spin on Peter Parker/Spider-Man’s origins and apply those to a story that’s set in the 1930s. While the 30s marked a boom period for the detective novel, most notably via the great Raymond Chandler, I feel like there’s more to the word “noir” than just an indication of a time, place and attitude.

Actual detective work is pretty hard to find in this story. There are some twists and turns regarding the allegiances of Ben Urich, Felicia Hardy and later Jonah, but it’s difficult for me to declare any of these plotlines to be compelling mysteries. And the book’s villain is pretty clear cut – it’s this Earth’s version of Norman Osborn, who goes by the street name the “Goblin,” and his gang of hoods (or circus freaks) which include the Enforcers, Vulture, Kraven and Chameleon. The creative team goes the extra mile in pushing the idea that Osborn and his crew are some of the most vile, despicable human beings to ever walk the Earth in the 1930s, but again, where are the mysterious shades of grey that you would find in a more traditional detective novel?

But my biggest issue with this series and its noir-ish sensibilities – and this will probably sound blasphemous on the surface – stems from the portrayal of Peter and his spider-powers. For a comic that’s supposed to have a vintage, smoky barroom feel to it, Peter becomes Spider-Man in fairly standard fashion. He’s spying on Osborn and his crew unloading a shipment of what turns out to be very creepy and deadly spiders, and is in turn, bitten by one of them and undergoes a transformation that gives him a set of superpowers that are never well-specified.

There’s nothing that feels particularly “noir” about Peter or Spider-Man in this character moment. Actually, quite the opposite, as Peter’s transformation is more mystical and fantastical instead of being grounded in the dark and gritty sensibilities that traditionally accompany a noir-inspired story.

I think an infinitely more daring and, as a result, more compelling story could have been told if the creative team eliminated the superhero transformation altogether, and instead just focused on Peter Parker, super detective. Whether he mystically has these powers that give him the ability to move faster or leap further than his adversaries seems like immaterial to me for a story like this. His “Spider-Sense” could just be a heightened instinct that helps him realize if a suspect is lying, or if he’s walking into some kind of set-up/frame-up.

Plus, the creative team here misses the boat with Spider-Man because they give him the powers but fail to hit on the responsibility in a meaningful way. They establish that Peter’s Uncle Ben was murdered by the Goblin’s crew because he was being a rabble rouser, but all that plotline succeeds in doing is motivating Peter for vengeance. There’s a scene later on in the story where Spider-Man kills the Vulture – actually, one of the character depictions that I really enjoyed in this comic since the creative team just goes full circus freak with Adrian Toomes and transforms him into a terrifying cannibal – and he’s made to feel remorseful because Aunt May tells the masked man that she doesn’t want to live in a world where people are just killing each other in the streets. But does this exchange really do the heavy lifting in terms of establishing why Peter would want to use his powers in responsible fashion going forward? I don’t see it, but maybe I’m just being dense.

Still – and this is why I can’t beat up on this story too much – Spider-Man Noir is one of the better alternative tale Spider-Man stories that’s out there. I don’t know if that’s more of an indictment about its competition, or just a qualified compliment from me. But it’s absolutely a fun read, just one that I think misrepresents that whole concept of the word “noir.” Take that word away, and just accept that you’re reading an alternative timleline Spider-Man story set in the 1930s, rather than some kind of Chandler-inspired detective tale.

I think you’re definition of “noir” is too narrow, mainly in regards to the detective aspect. Some of the most well-regarded noir classics – such as The Postman Always Rings Twice, Double Indemnity, and Strangers in a Train – have nothing to do with detectives or mysteries.

The main feature of noir is the dubious morality, like you said, but perhaps (and I haven’t read it, so I don’t know) having a Spider-Man who kills and never learned about responsibility may be enough to fall under that.