Amazing Spider-Man #530 is a significant entry in the title’s history because it’s the first issue that explicitly starts to outline the proposed parameters of the government’s Superhero Registration Act – a piece of fictional legislation designed to have Americans with super powers out themselves as part of a federal registry all in the name of “safety.” The SRA, of course, was a not-so-subtle reference to the Patriot Act and other assorted legislation that was enacted in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, and would be the central sticking point in Marvel’s “comic book life resembling real life” mega-event, “Civil War.”

Amazing Spider-Man #530 is a significant entry in the title’s history because it’s the first issue that explicitly starts to outline the proposed parameters of the government’s Superhero Registration Act – a piece of fictional legislation designed to have Americans with super powers out themselves as part of a federal registry all in the name of “safety.” The SRA, of course, was a not-so-subtle reference to the Patriot Act and other assorted legislation that was enacted in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks, and would be the central sticking point in Marvel’s “comic book life resembling real life” mega-event, “Civil War.”

It’s incredibly naïve of me to think this way, but I’ve always maintained that Spider-Man was a politics-free zone for me in terms of entertainment sources. In high school and college, I aspired to be a professional journalist (a goal I did achieve upon graduating from college), and while I would have been happy covering almost anything if it meant I had a daily byline in a respectable newspaper, I was a total political junkie, subscribing to every major political magazine I could think of like The Nation, the New Yorker, the New Republic and even the Economist for a period of time. I was incredibly passionate about the 2000 Presidential election, in large part because it was the first major election I was old enough to vote in, but also because I had convinced myself that modern civilization would end as we know it if George W. Bush was elected. We all, of course, know what happened there, and I remember writing an impassioned op-ed in my campus newspaper about the outcome, babbling about every conspiracy theory and perceived irregularity I could think of.

Then Sept. 11 happened, and while I maintained my political passion – in many ways it only increased – I also gained a laser-sharp focus on trying to capture the “story” of the moment, regardless of its political leanings. In many ways, this tragic event and the political and legislative fallout of it, helped shape me into a more moderate, balanced writer. Because of that shift, I had this unrealistic expectation that everything else that I consumed would shift alongside of me.

Of course Spider-Man has had political overtones going all the way back to its beginnings. Original ASM artist/co-plotter Steve Ditko was a notorious disciple of Ayn Rand and even worked some of her objectivism philosophy into Spidey – going so far as to having a crotchety Peter complain about student protesters wanting too much in Ditko’s final issue on the title. By the late 60s, the Stan Lee/John Romita Sr. run had Robbie Robertson’s son, Randy, talk about racial tensions and “the man” on the Empire State University campus. We also can’t forget Flash Thompson and his involvement in the controversial, generation-defining Vietnam War (and end up being worse for wear because of it).

Of course, Iron Man has always been the more political title. The existence of Stark Enterprises, the technology manufacturer, and the Iron Man character are owed to the post-World War II Military Industry Complex, which lasted through the end of the Cold War in the early 1990s. While Iron Man has taken on villains like Mandarin, Whiplash and Thanos, his most difficult adversary to subdue has long been the federal government, who have their eyes on Stark’s technology and its potential in the hands of the U.S. military. During Iron Man’s “Armor Wars” arc in the late 80s, Tony Stark and Captain America physically come to blows and destroy their friendship over the fact that Stark is trying to forcibly retrieve Iron Man technology from the government, which was stolen from his company by rival contractor Justin Hammer. As pro-capitalist and anti-communism as the Iron Man series has been throughout its history, Stark has also made it clear that his potentially deadly technology should never fall into the hands of outsiders, even alleged “good guys” like the U.S. government.

Spider-Man has certainly had his run-in with sanctioned authority figures, but his comics have always gone out of their way to make these individuals out to be clowns (like J. Jonah Jameson). Respectable authoritarians, like Captain Stacy, and even the police officer who found Spider-Man with Gwen Stacy’s dead body in ASM #122, never viewed Spidey as an adversary. So it’s certainly an interesting choice by J. Michael Straczynski to use Peter Parker/Spider-Man as Stark’s sidekick in Washington, D.C., in ASM #530.

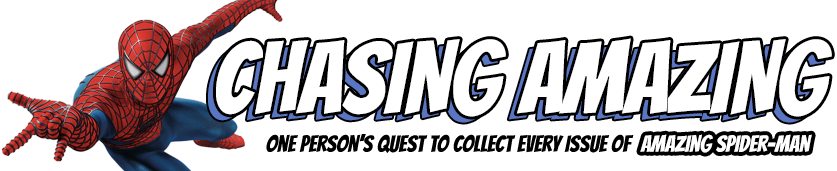

Probably the most notable scene in the issue came during the Congressional hearing. The politicians are pushing Stark about the amount of damage superheroes have caused the federal government since World War II and how a federal registry, a la doctors and other professionals, would help hold heroes more accountable for their actions. Stark’s reaction is naturally, to be flippant and remind the politicos about all the times superheroes have saved the United States and the entire planet from vaporization and destruction.

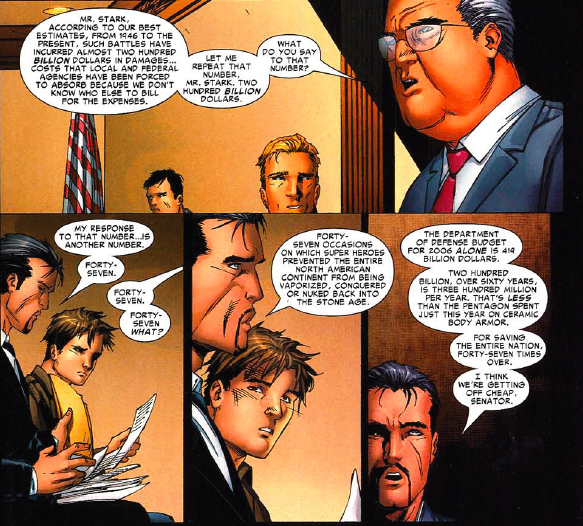

Peter, not having that kind of adversarial relationship with the political “man,” gives a passionate plea about “power and responsibility,” and how those tenants apply to more than just confrontations between heroes and villains. Peter, is of course, referencing people like his Uncle Ben and Gwen Stacy – family and loved ones of heroes who were killed or badly hurt because a villain or some other force of evil was able to use a hero’s identity against them.

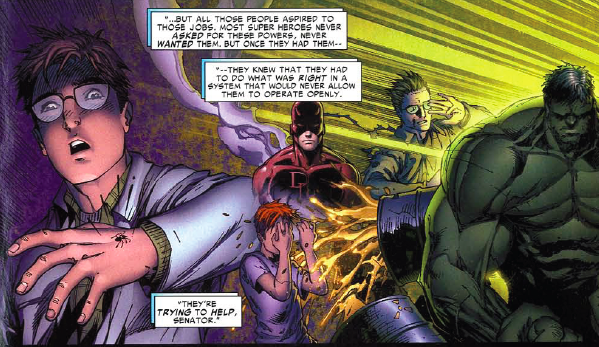

It’s the kind of speech you would expect from Peter Parker in front of Congress, but this being a story that’s as much about Iron Man/Stark as it is Peter, ends up being Parker’s undoing. The politicians turn his argument on its ear and make the case that Peter’s scenario make it all the more important for heroes to work closely with the government for the good and protection of everyone. From that point on, Stark tells Peter he needs to train him better on the art of talking to politicians – something I was able to relate to from my time as a professional journalist.

On one hand, having an issue of Amazing Spider-Man that’s centered so squarely on the real-life political situation in the United States makes for a unique and interesting reading experience. Even when considering the aforementioned ASM storylines where things got political, those were still comics with political “moments,” not overtly political comics.

ASM #530 shows a clear delineation of the relating-to-real-life themes that have defined Spider-Man and Iron Man comics. Peter’s reasons for being Spider-Man have always been personal, and he’s almost always reacted naively to those who don’t see his actions as “good.” Whereas Tony is much more calculating and manipulative in everything that he does (and these themes become even more apparent in the arc’s final issue, which will be posted Monday). For both heroes, it’s still all inevitably about “power and responsibility,” but with differing applications and expected results. Peter wants to speak truth to power, while Tony needs him to play his part better.

This is the second part of the “Mr. Parker Goes to Washington” arc. Click here for Part I/III