I’m almost starting to feel bad for Flash Thompson.

Which, I guess is exactly Rick Remender’s point with his work on the Venom series. While Flash was first introduced to Marvel audiences as one of Peter Parker’s main antagonists, like a lot of fictitious schoolyard bullies, time and maturity took over and transformed Eugene into one of Peter’s closest friends. However, that didn’t change the fact that Flash was also a first-class knucklehead, who couldn’t get out of his own way and who has plenty of personal demons to overcome.

Still, my heart sank a bit towards the end of a very twisted two-story arc across issues #11 and #12 that featured Flash/Venom and the psychotic Jack O’Lantern traveling out west to Las Vegas to do some dirty work for the Crime Master. After getting over the morbid image of two innocent diner employees getting their brains scooped out by Jack (sorry, as I explained during my write-up on Carnage, I’m still a little squeamish with gore), there’s the news reports following the confrontation between the two characters which identifies both as “supervillains.”

If you told me 10 years ago that a character played by Flash Thompson would go on to be Marvel’s next big supervillain I would have laughed (this is discounting the time Flash was framed and mistakenly identified as the Hobgoblin). But that’s what Remender manages to do every issue in Venom – it makes you reconsider the potential depths of a once dismissible character.

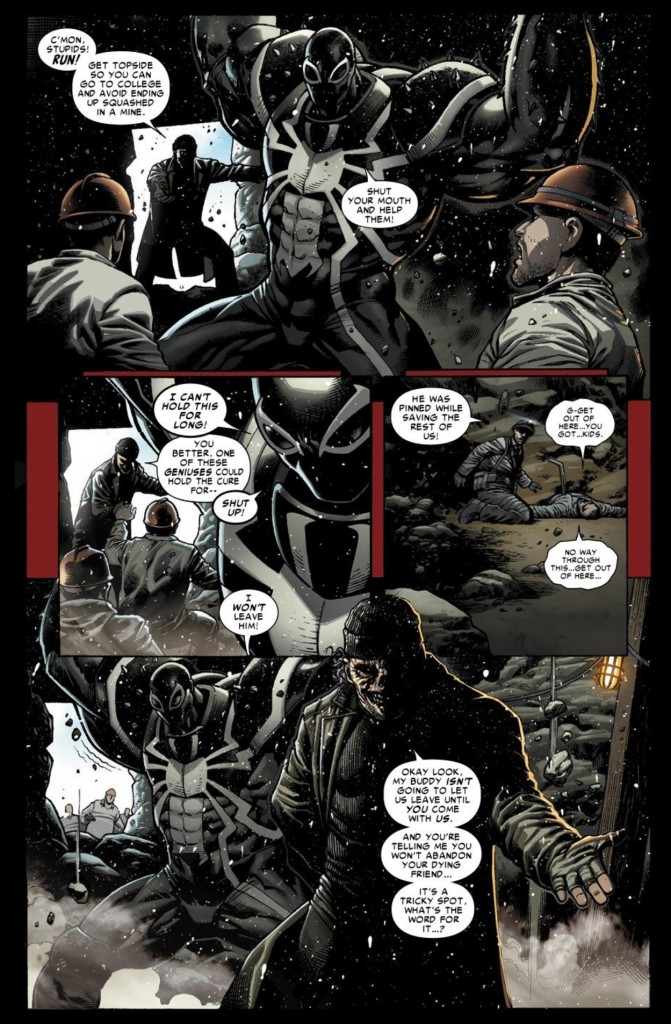

This is what we know – Flash is not inherently evil. An argument could be made that the symbiote that creates Venom is not inherently evil. By definition, the symbiote is a survivalist. It aspires to bond to other lifeforms in an effort to sustain itself. Without a host, it will wither and die. When Peter Parker was bonded to the symbiote, there was never any question that he was still playing the hero. It was until the symbiote bonded to a character with evil intentions in Eddie Brock, who wanted to exact violent revenge on Spider-Man, that the character displayed true intentional malice for others. And even now, with Brock playing Anti-Venom, his motives are questionable. That’s because regardless of what kind of alien substance is powering him, Brock is a suspect individual. A fascinating one. But a suspect one.

As I alluded to earlier, Flash’s personality issues stem more from his personal demons, than any inherent maliciousness. He’s your classic emotionally abused kid who never had a proper role model. He goes off to war to become a hero, and he comes back to the U.S. missing his legs. He finds true love in Betty Brant and he has to break up with her because he’s an alcoholic who can’t regain control of his life. The symbiote gives him unimaginable physical power, but he only comes across it to perform black-ops duties for the government. He only wanders into questionable ethical territory when he refuses to surrender the costume back at the end of his mission.

These are not the characteristics of a supervillain either way, and while I know that’s exactly Remender’s point – to demonstrate how public perception writes the narrative more than facts – I just feel better getting those words onto a page. As we cross into this Circle of Four storyline, which will unite Venom with a host of other questionable anti-heroes, I’m going to be paying close to attention to see if they continue to push Flash further down the black hole of villainy, or if they’re going to keep reminding us of the troubled youth who just can’t get his act together.

All images from Venom #11-12: Rick Remender, Lan Medina, Nelson DeCastro & Marte Garcia. Cover by Tony Moore & Morry Hollowell