A pair of dueling columns on the web site Bleeding Cool recently explored the idea of how politics may be negatively impacting comic book sales (which continue to spiral downward). While I could dismiss the whole argument by saying it has nothing to do with “Liberal” and “Conservative” but rather a growing digital market that is killing print and advertising revenue in a variety of ways, but what fun would that be?

I’m not going to take a side in this argument, though I will add that reading these two columns spurred me to look back at a couple of moments from the mid-1960s when ASM writer Stan Lee chose to take an apolitical stance on one of the nation’s most controversial topics.

The Vietnam Wars was one of those moments in history that was so divisive, presidential candidates are still dealing with the repercussions 40+ years later. The entire 1992 campaign between George Bush and Bill Clinton was centered around the culture wars which were first conceived during the Vietnam War-era, and an argument could be made that just four years ago, the Barack Obama and John McCain election was more of the same. These culture war arguments mark a generational divide and considering the vast amount of people who were teenagers or adults during this era are still alive and haven’t gotten over this divide to this day, the contentiousness is not going to disappear anytime soon.

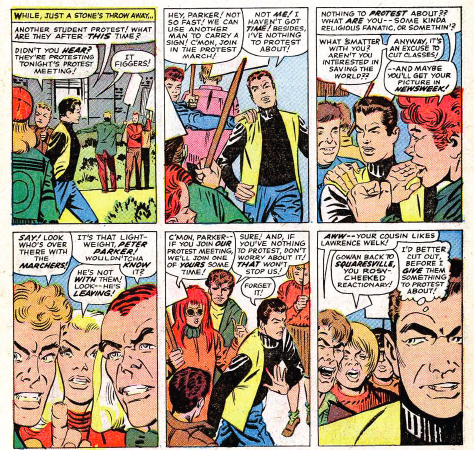

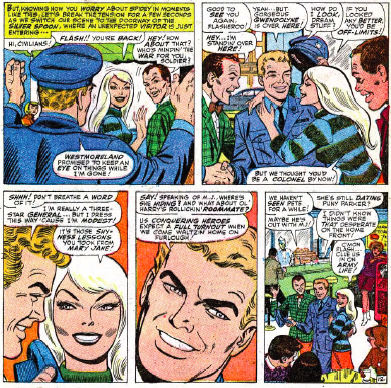

Yet, the first few mentions of the Vietnam War in the pages of Amazing Spider-Man are more comical than anything else. Readers are treated to a protest in ASM #38, yet nobody knows exactly what they’re protesting (similar types of arguments have been made about the “Occupy” movements). When Flash Thompson returns in uniform from his first tour in Vietnam, he’s celebrated by his friends, but the actual impacts of “war” are largely ignored (though we’d obviously see the fallout for Flash in comic book form at later date).

I was so stunned by the lack of controversy in these two issues (ASM #38 and #52) that I had to read and re-read to get a sense of some kind of hidden political agenda in there. If there is, I just don’t see it.

Was Spider-Man/Peter Parker a liberal or a conservative? We don’t know in these specific issues and quite honestly, I prefer it that way. I did find Rich Johnston’s thesis about conservatism in comic books to be very insightful:

But as as a genre, the superhero is very conservative indeed. Though this can be interpreted in different ways. They stop bank robbers or other super villains dressed in a similar fashion, they don’t try to alter the causes, create a world where people don’t want to be bank robbers or super villains. Proponents of law and order, but not part of big government, they emphasise individual responsibility over statism, in keeping the world as it is, simply dealing with the side effects of that. In a universe where the Fantastic Four can create portals into other dimensions, robots and all manner of otherworldy devices to beat the bad guys, they don’t eliminate poverty, they don’t create free, environmentally friendly energy. Any attempt by someone to do such a thing, and solve real world problems such as people losing limbs, has their laudable aim backfire on them and they become a super villain like the Lizard. But why?

Which is why when a comic book company has one of their characters talk out against “Big Oil” or renounce their U.S. citizenship, I can understand why it grates, because it seemingly bucks the traditions of the genre by giving these characters essentially too much of a voice. When superheroes have a cause, it tends to be preserving freedom, justice and safety for all of its citizens. Sounds like the last Republican Nomination Convention if you ask me.

Yet, looking back at these earlier comics from the 1960s, many are celebrated as some of the finest cases of storytelling in the genre’s history, yet politically-specific conversations are noticeably absent. At the time, did we really honestly care whether Peter Parker had an opinion about America’s occupation and activities in Vietnam? At the time, did we need to hear about the horrors of war as witnessed by Spider-Man’s long-time playground nemesis?

However, because we are more attuned to political discussion now than we ever were before – thanks in large part because of the explosion of media that are indirectly destroying print such as cable television and blogs – we know have these dueling counterpoint conversations on comic book web sites. When Dan Slott makes an Occupy Wall Street joke in a recent issue of ASM, I chuckled, but try not to read too much into it. I hope that ASM manages to keep these comments on the periphery.

Given the strongly anti-Communist tone of early ’60s Marvel, it seems to me that the early mocking of the protests was not apolitical but anti-anti war (but Lee may have grown more sympathetic, including in his depictions, later on). The characters don’t need to be and shouldn’t be strident on a lot of controversial issues but it would be less realistic and less interesting if they (perhaps especially Peter Parker, working for a newspaper albeit through action photos) avoided having thoughts or discussions on at least some.